What’s up?

Quality grades… and a new research paper explains why

By Miranda Reiman

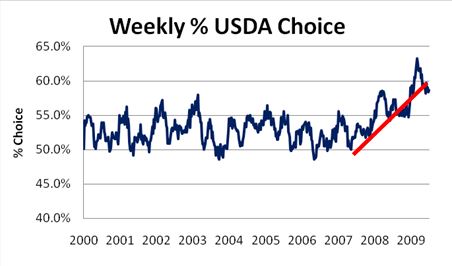

Three years ago, a 30-year decline in beef quality grades was apparent, with only half of fed cattle grading USDA Choice. The Choice/Select spread hit record highs in 2006, but today the picture is much different (see chart). July figures show 60.1% of the harvest mix graded Choice the first half of this year, but why?

Certified Angus Beef LLC (CAB) animal scientists recently authored a research paper on those trends. “Quality Grade: What is driving the recent upswing?” by Larry Corah and Mark McCully, delves into regional differences, how quality improved so quickly and why it changed.

Nationwide, the share of Choice grading cattle made a 7.5-percentage-point leap in just two years.

“The main reason for that rapid shift is that a large number of cattle marbling scores are very close to the USDA grading lines,” Corah, CAB vice president, says. Just adding 20 more units of marbling, going from Slight-80 to Small-0, results in 5.71% more cattle grading Choice.

“That seemingly tiny change has an even greater impact on those qualifying for the Certified Angus Beef ® brand,” he says.

After a low of 14% CAB acceptance in 2006, the brand will beat 19.5% during this fiscal year. That’s nearly a 40% increase in three years.

The Central Plains show the greatest improvement and distillers grain byproducts might be part of the answer, although potentially part of the problem if they get above 40% of the dry-matter ration content. By 2007 these byproducts were fed in 82.5% of feedlot rations, but at a moderate 15% to 30% level.

When held to those levels, research shows distillers corn byproducts actually result in higher grades, partly by increasing appetite, and especially in starter diets.

“Higher dry-matter intake, better calf health and higher daily gains support higher quality grade,” says McCully CAB assistant vice president, noting that Elanco Animal Health Benchmark® Program data reveals positive trends in all of these areas.

That’s coupled with herd liquidation, which has boosted the heifer share of the harvest mix to 37.4%, a few points above normal.

“Heifers tend to grade 9 to 10 points better than steers, so that may account for at least a half a percentage point increase overall,” he says.

Use of Angus genetics is on the rise and at the same time, the expected progeny difference (EPD) for marbling score in Angus has moved up 7 points since 2004.

“It only moved 9 points in the first 25 years of the EPD’s existence,” Corah says. Angus bull usage increased from 39% to a 55% share of all bulls from 1994 to 2008, and nearly 70% of commercial cows are now considered primarily Angus.

Iowa feedlot futurity data shows only 52.7% of calves with less than a quarter Angus breeding grade Choice, compared to their counterparts that are at least three-quarters Angus, at 86.2% Choice and Prime. CAB acceptance rate nearly quadruples with the greater Angus heritage.

Although quality grade is hard to predict, this grading surge might stick. That doesn’t mean producers counting on grid-based premiums should be discouraged.

“If quality grades do not decline within a year, it could mean the infusion of higher-marbling genetics has had a lasting effect,” Corah says. “Coupled with smaller cattle numbers, consumer demand in a recovering economy will likely drive the Choice-Select spread to higher levels.”

To read the entire paper, visit https://cabcattle.com/about/research/