Fine-tuned engines

Beef scientists share mineral supplementation strategies.

by Maeley Herring

August 13, 2020

Under the hood of a pickup lies an assembly of metal, its details often forgotten – until the motor breaks down. All that’s left is a vehicle that can no longer do its job.

Mineral nutrition in cattle is kind of like that.

Hidden beneath the hide, minerals act behind the scenes to maintain general function. When cattle can’t access all the minerals they need, reproduction rates drop, tissue growth diminishes and illness sets in.

That’s why mineral supplementation underpins any cattle operation.

Breaking it down

“Every biological process in cattle involves minerals,” Stephanie Hansen said at the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association “Minerals 101” webinar in July.

Everything. Of course that includes health, feed efficiency and reproduction.

Less obvious? “Things like marbling, ribeye area development and muscle fiber type,” the Iowa State University feedlot nutritionist explained.

Topping off the minerals helps all functions, but quality beef starts with the cow.

“The dam’s nutrition program can have huge effects on carcass quality or heifer reproduction in the future,” said Jeff Heldt, beef technical services manager at Micronutrients, in a later interview. The healthier the cow when bred, the higher chance her calf will realize its potential.

That only gets more important in the following months.

“In the last third of gestation, that fetal liver is accumulating trace minerals that meet its basic mineral needs for the first three to six months of age,” Hansen said. Beef-cow milk is low in trace minerals, so newborns have to pull from nutrients stored in their liver.

For the weaned calves on wheat or those placed in finishing yards, mineral nutrition helps ensure they never have a bad day.

Weaning, shipping and changes in environment are critical times, Hansen said. Calves in transit lose less and rebound faster if they’ve had adequate trace minerals.

Avoiding roadblocks

Sounds easy enough, but how can you tell if it’s all on track?

“Measuring success or failure in mineral nutrition is often very challenging,” Heldt said. Add protein to the ration and you’ll see an increase of gain. “But you feed a hundred milligrams a day of copper, and there’s no obvious response or physical observation.”

Planned programs can help.

Knowing the amounts of mineral types in feedstuffs, requirements for cattle, and absorption rates ensures cost effectiveness, Hansen said.

All forages contain minerals, but content varies much by species, maturity, soils and climate.

“If you’re thinking about developing your own supplementation program—a great way to be cost effective—testing your own forages can be really important,” she said.

To get the full picture, test water sources for antagonists like sulfur or iron that disrupt mineral absorption in the rumen.

“Half of the mineral in forage is actually available to the animal,” Hansen said, noting digestibility, maturity and antagonists.

“Find a baseline,” Heldt suggested.

Knowing average mineral content in forages and any antagonists present opens the gate to cost-effective supplementation.

Staying on course

It can be hard to invest in something without obvious or immediate results.

The need for minerals is plain enough, but figuring out what and how much to supplement seasonally? Not so much, Heldt said. It’s an added cost that takes time to distribute and monitor.

That’s why convenience comes first in creating a plan to follow.

“You can design a pretty in-depth, extensive mineral program and easily overcomplicate it,” he said, advising to keep it easy and simple “to make sure it gets done.”

Worrying about the cost-benefit ratio can get in the way, too.

You’re more likely to stick to a program if you know the importance of minerals at every level, even basic grazing, where they can improve fiber digestion.

“Forage – pasture grass, hay, wheat – is the core feed base for any ranch, and the mineral source can positively affect fiber digestion, setting cattle up for future success,” Heldt said.

Mineral supplementation requires a time and monetary commitment, but it’s worth it to keep what’s under the hide running smoothly.

You may also like

$100,000 Up for Grabs with 2024 Colvin Scholarships

Certified Angus Beef is offering $100,000 in scholarships for agricultural college students through the 2024 Colvin Scholarship Fund. Aspiring students passionate about agriculture and innovation, who live in the U.S. or Canada, are encouraged to apply before the April 30 deadline. With the Colvin Scholarship Fund honoring Louis M. “Mick” Colvin’s legacy, Certified Angus Beef continues its commitment to cultivating future leaders in the beef industry.

Raised with Respect™ Cattle Care Campaign Launched This Fall

Raised with Respect™ was developed as part of a strategic cattle care partnership between Sysco and CAB. The collaboration focuses on supporting farmers and ranchers, equipping them with continuing education to stay current on best management practices and helping to increase consumer confidence in beef production.

Drought Impact and Cattle Industry Dynamics

As drought conditions persist across much of cattle country, farmers and ranchers are at a pivotal juncture in the cattle industry’s landscape. What impact does this prolonged dry spell have on the nation’s herd numbers? When will heifer retention begin? How will industry dynamics influence the spring bull sale season?

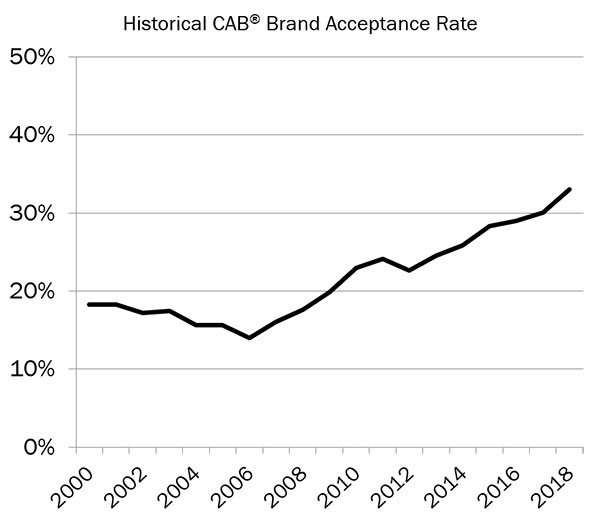

The Angus influence has grown steadily in the last 20 years. In the 1990s, about a third of the herd was black hided versus roughly two-thirds today.

The Angus influence has grown steadily in the last 20 years. In the 1990s, about a third of the herd was black hided versus roughly two-thirds today.